The below story comes from an 1897 issue of the ‘Distillers’ Magazine and Spirit Trade News’. It is written by J Gordon Phillips who also wrote ‘Wanderings in the Highlands’ and had met local characters such as Eppie Thain in person.

It retells two stories of the exploits of the Glen Nochty smugglers and goes onto greater detail about how stills were set up.

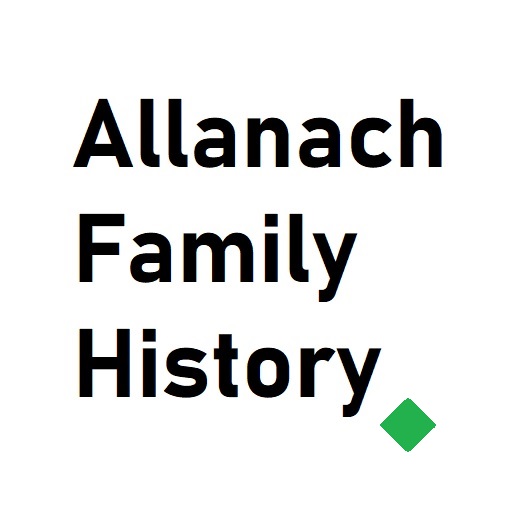

Interestingly it also has a lovely illustration of the incident with the gaugers and the red coats; I have tried to lighten it for the cover photo as it appears quite dark in print.

We will never know if the Allanachs were involved in either of these instances. However, we do know Allanachs were arrested in 1797 and in the 1820s for whisky smuggling and ‘rioting’ so they were certainly in the area and engaged in smuggling during the time the incidents happened. As such, if they were there on the day throwing rocks at the gaugers, we will likely never know, but were they part of the ‘Glen Nochty boys’ smuggling gangs, almost certainly.

“This is no concocted story, but was told to me by a hard man of the world in the presence of another gentleman. On that occasion the excise officers visited that stream, and passed within a few yards of the bothy, right along an old road which winds over a steep hill called the Ladder, and into Glennochty, in Aberdeenshire, which was another nest of smugglers. They were a fierce and a desperate set of men, too, those Highlanders of Glennochty, ready to do battle with all and sundry whether they were preventives or excisemen. On one occasion a large force of preventives, along with a number of excisemen, went scouring up Nochtyside destroying a number of bothies, spilling whisky, and generally creating a complete wreck. The Glennochty men retired before them up the hill in the direction of Glenlivet, at the same time despatching one or two of their best runners to warn the Glenlivet men, and to ask their assistance, as they meant to make a stand in the Moss of Mousach. The place so called is a deep and dangerous morass or peat bog, which has gradually grown and filled up a mountain tar which lay on a flat near the top of the Ladder hill. It is a dark and gloomy spot, associated with wild Highland legends and traditions connected with the supernatural. I have listened to stories of Mousach by the…

...winter fire which made the flesh creep, and in going outside in the dark there was an eerie feeling which kept me looking over my shoulder and whistling, in case some fiend or spunkie (1) should catch me unawares , It will be remembered Tam o’ Shanter did the same thing when cantering home from Ayr. It was in that dismal, ghoul-haunted spot that the men of Glennochty proposed to meet the excisemen who had destroyed their goods. The messengers which they had despatched, fortunately perhaps, did not find many Glenlivet men, otherwise the fight would have probably turned out more serious than it did. It was serious enough, but there was no actual loss of life, though there were plenty of broken heads. Being taken in great measure by surprise, the smugglers had no firearms, otherwise there would have to a certainty been slaughter, for they were exasperated and desperate, ready to do anything. The row began by the leaders of the excisemen calling upon the smugglers to surrender or they would shoot them. There were not half the number of smugglers, but they had taken up a position in the morass which the excisemen without knowing the ground could scarcely reach. The smugglers laughed, and told them to come and take them. They knew what they were doing. The officers advanced and entered the dreaded morass. Then the smugglers opened out, divided in the middle, and fell upon the flanks of the officers. They were armed with heavy sticks, and in a few minutes there were a dozen preventives. and excisemen lying in the Moss of Mousach. They were not seriously damaged, simply knocked down. Several of the officers tried to use their swords, and some men were hit, but the position of the exciseman was so awkward that it was not easy to use weapons of any kind. However, in a short time they were in full retreat down the hill, pursued by the victorious smugglers, who pressed close upon their heels so as to prevent them from using pistols. Whenever an officer turned a shower of stones went singing round his head. Latterly the flight became a complete rout, and the smugglers followed closely, jeering until they chased them out of Glennochty into Strathdon. There they left them, and returned to repair their bothies as best they could.

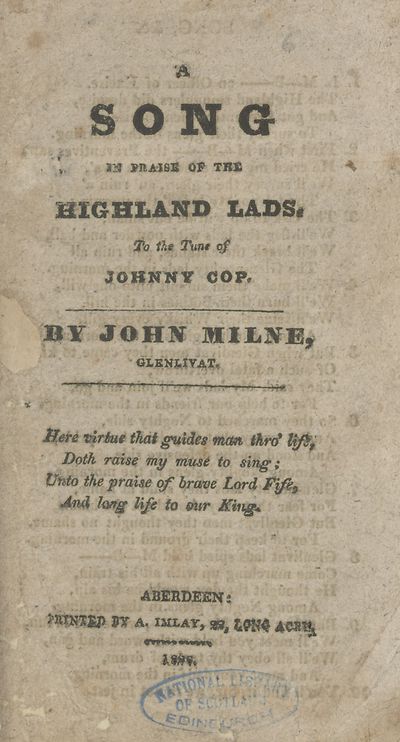

This fight, however, was to have important results. It had gone so completely against the Revenue officers, with the exception of what they had destroyed, that they might have been inclined to let it pass and say as little about it as possible, waiting for another day to revenge themselves This was not to be, however. A local rhymster known as John Milne o’ Livet Glen, wrote a lengthy effusion, got it printed, and had it scattered broadeast over the country. As John, who was a most inveterate smuggler himself, attended all the fairs and mang his own productions, it was not difficult to circulate ” Nochty’s Glen in the Mornin’ which was the title of the piece. John’s imagination, though not of a high order, was fervid enough, and his sympathy being altogether with the smugglers, there is no need to say that he made the most of the incident, and the fight in Glennochty assumed the proportions of a Waterloo or a blood-red field of carnage. The outcome was that some copies of the ballad reached Edinburgh, and the authorities thought that there was something like another rising in the Highlands. At all events they saw that the authority of the law was being set at defiance, and that the Revenue men were unable to cope with the smugglers. They applied to the War Office, and a few companies of soldiers were immediately dispatched to Corgarff, in the head waters of the Don, where they took up their residence in the old castle. From this point they could march over the Leicht Hill into the Braes of Conglass at Blair-na-Marrow (i.e., Field of the Dead), and from that point cross into the Braes of Glenlivet. Or they could march right down Strathdon and turn west into Glennochty. The position was altogether favourable for the operations they were called upon to carry out, but like the excisemen with the preventives, they did not like the work, and as a matter of fact they never did anything in the way of fighting though there was no lack of opportunity. I remember an old smuggler telling me an anecdote which well illustrates this, and how difficult it was for preventives sometimes to do their duty.

“There were five of us,” he said. “The gaugers had suddenly crossed the hills before warning could be sent to Glenlivet, and it was by the merest accident that we were not captured and all that we had taken. It was in the early morning, and, as it happened, a girl who went to the well to fetch water noticed a body of men advancing, and about two hundred yards behind them another body with red coats. She immediately knew what was the matter, for though the military had not appeared before in Glenlivet until that morning, it was very well known that they were stationed in Corgarff, and a visit might be expected from them at any time. The lassie threw down her pail and fled swiftly to the nearest bothy. The preventires saw her, and saw suspecting what she was about, shouted to stop. She never looked behind, but sped onward. When near the bothy she cried in Gaelic, “The gangers, the gaugers, and red-coats.” We heard her and cleared out, and had began to climb Benmore before the gaugers turned the corner, so they followed sharply after us, never pausing to look for the bothy . There was about thirty of them, and behind them at a little distance marched the soldiers with their guns on their shoulders. We had run up the hill as far as we could, for we thought that the soldiers would shoot. The gaugers followed hard, shouting all the time to stop. Breathless, we sat down on the top of a crag, gazing at the advancing excisemen. It appeared to us that unless we could weary then out by running in the hills there would be little hope of our escaping. Fancy our surprise when the officer in command of the soldiers shouted in Gaelic, “” Why don’t you roll down stones on the devils ? ”

We almost gave a cheer, but we were afraid that the gaugers would understand if we did so that the officer had given us instructions . But we were not long in setting to work, and it was amazing how nimbly those men leaped when a stone went bounding down the steep heather slope, crashing and twisting here and there, and no one knowing which way it would turn next. The gaugers shouted to the soldiers to fire, and gesticulated wildly when a stone bounded past their shins, but the soldiers stood at a safe distance, evidently enjoying the sport. They never took their guns from their shoulders. The gaugers beat a retreat to the bottom of the hill, and we sat on the brow. We were too few to follow them, and though the officer had cried to us to roll down the stones, we did not know how far we could carry the joke. At any rate, we thought it better to be on the safe side. We afterwards heard that the officer belonged to Braemar, and that both he and the private soldiers were thoroughly disgusted with the whole thing. The smugglers of Corgarff soon found that out, and, believe me, as long as the red-coats occupied the old castle they never wanted a drop of good stuff. They much preferred that to hunting poor men like us who were only trying to make a living the best way we could. We thought we were being very hardly used by the Government, but then we had not much idea of things in those days.”

The old man who told me that story was a fine specimen of his race straight as a Highland pine till the day of his death, and he stood about six feet two. He sleeps in the quaint little burying-ground of Chapelton, in his native glen, close by the flashing Crombie and under the shadow of the Benaven mountains. Next month I shall tell some of the struggles between the excise officers and the smugglers on a larger and more desperate scale, when blood was freely shed and some gallant and heroic deeds were done.

(1) You can find out more about Spunkies and other Scottish ghoulish creatures in this podcast by Stories of Scotland