This Halloween it is easy to think of folklore as something from the imagined past/ created present. That witches have green faces, cackle and either live in Oz and wear ruby slippers or are imagined creatures flying around on broomsticks for the sole purpose of scaring children.

But to our ancestors witches were very real, and the consequences of being accused could see you burnt at the stake.

I have taken a look at Strathdon, where the majority of Allanachs resided at the time of the witch-hunts, and have found a lot of first-hand documentation that I will explore below.

Witchcraft has older roots in Scotland, but their investigation reached a peak under James VI, and whose legacy lives on today in literature, such as Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

Bruce Fummey explains this brilliantly on his Youtube channel :

Much work has been done to map the Scottish witch trials. The University of Edinburgh has a map of the places of residence of those accused of being witches or warlocks.

Superficially it looks like the Cairngorms is a ‘witch free ‘ zone, with just one trial – that of Marion Quhite (White) in 1626.

But again, the reality was somewhat different. In Strathdon and surrounds, the Catholic religion still held sway in the 1600s, so the Puritan zeal to find witches many not have been as strong.

Secondly, looking at the map, there were far fewer witch denunciations in the Highlands than in the Lowlands. This is likely because in Gaelic culture, folklore and superstition, included witchcraft were part of everyday life. There was both a fear and a respect for witchcraft, and you see this again and again in oral records. Listen to this example , recorded in 1956 with a crofter over the Ladder Hills from Glen Nochty, where Rachel Macgregor told the contributor that sometimes a white hare turned out to be a witch. Rachel had no fear of witches or fairies. Old women who had second sight were not regarded as witches, but were respected.

The above example shows that beliefs in witches (and Kelpies, faeries and the myriad of other creatures in Scottish folklore) existed well into the twentieth century (indeed maybe until present!).

It is difficult for us to imagine now, but these beliefs would have shaped the pattern of the year, social interactions, agricultural life etc.

Allanachs and witchcraft accusations

We are fortunate here that a folklorist called Walter Gregor visited Strathdon and Corgarff, and recorded the accounts he heard. It may surprise you to hear that this was in 1889 – a couple of years before the first car would drive down the road past the houses of the persons making the accusations!

There are so many accounts, I could probably write a whole dissertation on it, but for now I will concentrate on witches and save other creatures/ tales for future Halloweens!

His volume on Witches in Strathdon and Corgarff is available on WIki here.

Two stories stand out. Others may come to light as I work out who the persons are that he has anonymised by using initials!

Firstly – a tale of a devil-like witch from Dalrossach – a croft inhabited by James Allanach (different to the James Allanach in story 2), and his wife Isobel Rannie, and where Captain George Stuart (Allanach) was born in 1820. In the listing for Captain George, there is a photo of what the road looks like today, should you want to imagine what it would look like with a demon creature scuttling across it!

“If one gets the “first word” of a witch, or of one having an “ill fit,” or any supernatural being bent on evil, all power to injure is taken away. J— R—, a farmer in Strathdon, was returning home one wild stormy night in winter. When he came to a place called Dalrossach, he saw a creature that looked like a child cross the road in front of him. He at once cried out, “Peer (poor) thing! Ye’re far fae hame in sic a stormy nicht.” The creature disappeared. The farmer was convinced that mischief was intended to be done to him”

Secondly, a tale of tryng to undo a witches spell. Again from Strathdon

“Mrs. Michie, Coull of Newe, Strathdon, began one day to make butter, but no butter could she get, though she churned from three o’clock in the afternoon till late at night. The cream was given to the pigs, but they turned away from it. On three separate occasions the same thing took place. Something was judged to be far wrong. Peter Smith, a man of skill, that lived in the adjoining parish of Towie, was sent for. He was fond of a glass of whisky, and on his arrival he was treated to one and a little more. So refreshed, he said, “Noo (now), a’m (I am) fit for wark (work).” He asked if there was any myrrh in the house. There was not. My informant, Mr. W. Michie, the present farmer, then a boy, was sent to the gardens of Castle Newe—not far distant—in search of the herb. He got a small quantity. The “skeely man” examined it, smelt it, and said, “There’s nae muckle o’t, bit (but) its gueede (good).” He then ordered a large copper to be placed over the fire and half filled with water. He put the myrrh and some ingredients he took from his pocket into the copper. He sat down and watched the mixture boiling for about three hours. The copper was then removed from the fire, and the mixture was allowed to cool. When it was cooled, a bottleful of it was given not only to each cow, but to each of the cattle on the farm. A small stream, or “burn,” runs alongside the farm. He asked Mrs. Michie to go to it and to gather from it a quantity of “water-ryack” and to place it over the door of the cowbyre. He gave instructions that if there was any difficulty (which there might be) in the butter -making when the cream was next churned, a little rennet should be put into the churn. He asserted there would be no difficulty again.

Mrs. Michie asked Peter if he knew who had wrought the mischief. He said he did, but he refused to tell her as “it wid (would) only cause dispeace amon’ neebours (neighbours).”

He was in the habit of saying that he had got the secret from his wife before she died, and that he could give it before he died to a woman. It was the common belief with regard to these occult powers that they could only be given just before death to one of the opposite sex. (Told by Mr. Michie.)”

So who were the neighbours he was defacto accusing?

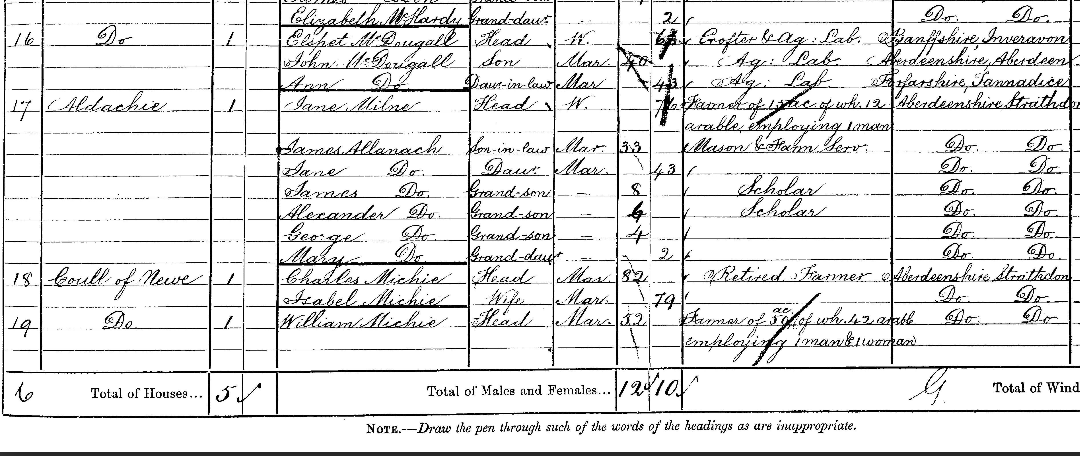

Well, the census data shows us it was James Allanach and his family!

Lastly, outwith Walter Gregor’s work, there is perhaps one of Scotland’s best known ‘The Witches of Delnabo’. There is a possibility of an earlier Allanach link to one of the nearby farms mentioned in the tale but research still ongoing.

So – there we have it! The world the Allanachs in which the lived in 1700s and 1800s Strathdon would definately have been full of superstition, rite and folklore belief, with some of the accusations being directly aimed at the Allanachs themselves.

Perhaps when guisers and trick n treaters knock on Allanach doors, they might need to be careful of playing tricks on us – we might just have a spell up our sleeves! 🙂