Ian Allanach

Ian Allanach or John Stewart

The below Allanach certainly led an interesting life but sadly the only find record I can find of Ian Allanach (or John Stewart) is as an extended story in Deeside Tales.

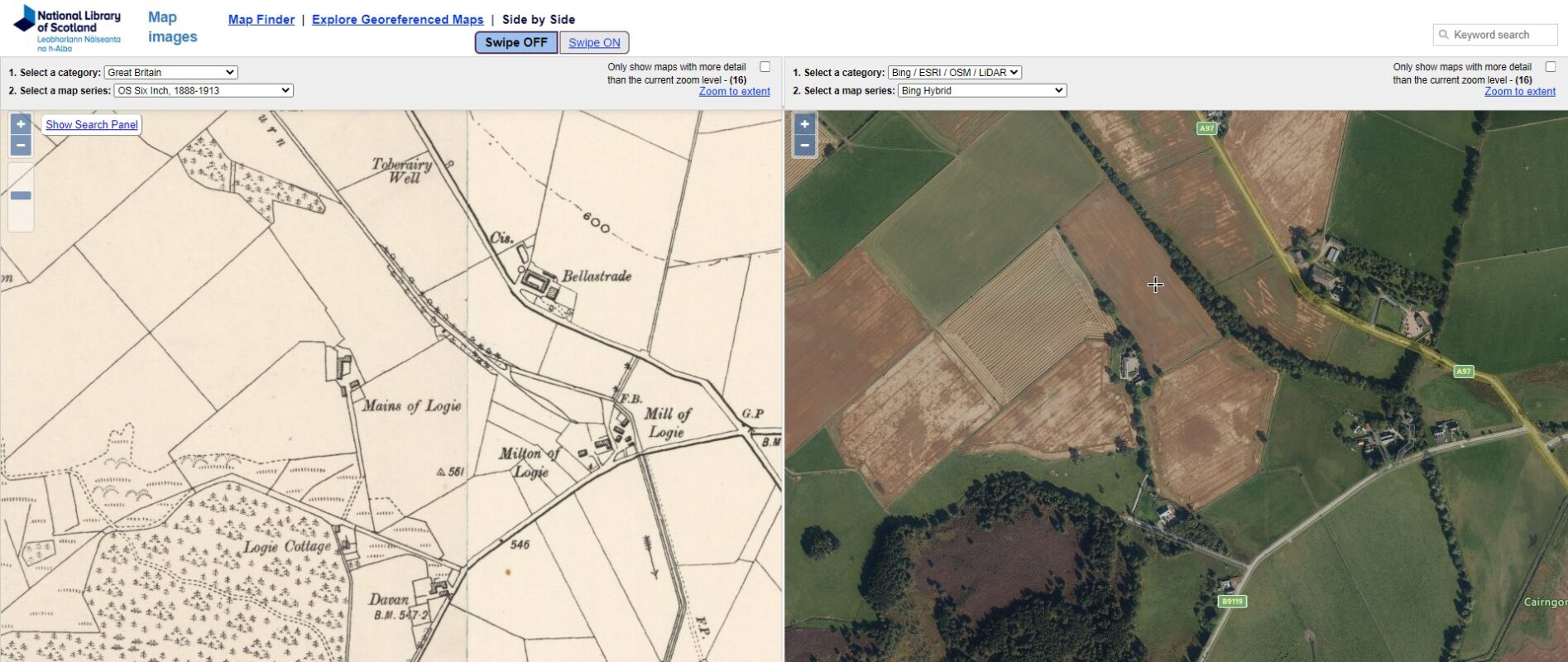

Deeside Tales was first published in 1872 by John Grant Mitchie of Coldstone. He refers to Ian living in the hamlet of Bellastraid, in the parish of Logie Coldstone.

Given he refers to him surviving 90 winters on his death in 1833, I have put Ian’s birth as 1743.

This would have made Ian 18 at the time of the Battle of Vellinghausen in 1761. In the tale below, it is told that Ian would often remember his time in the army fondly and tell many a yarn around his neighbour’s fireplace on cold evenings. The truth might have been somewhat different, however. Many children were kidnapped or press-ganged to serve in the army, and this might have been the case for Ian too.

The below is also an interesting example of language shift in Scotland. It is written that Ian is a fluent Doric speaker (and likely from his name Gaelic too) but that when he wants to use certain modern expressions he attempts an English accent. Scots is also referred to as distinct from Doric.

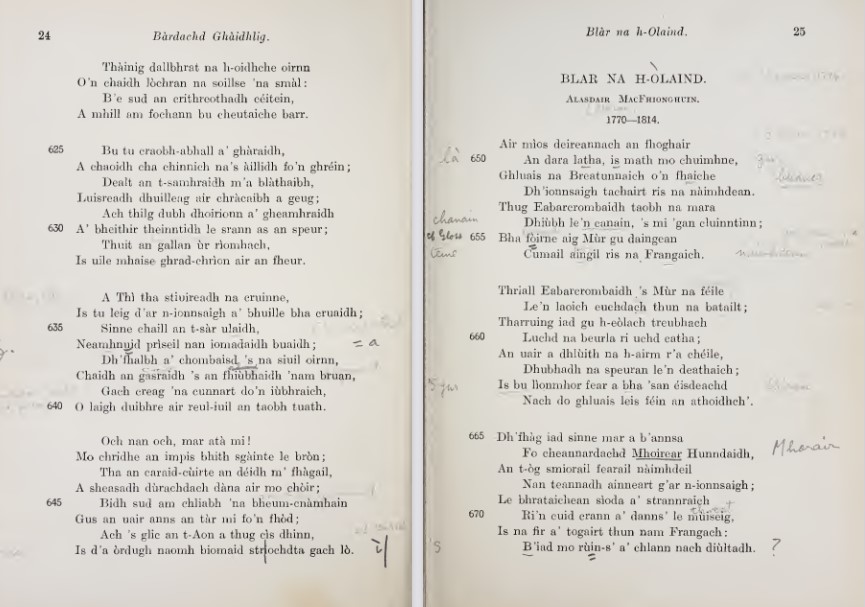

Iain is also referenced in a poem ‘Blàr na h-Òlaind (Battle of Holland)’ by Alasdair MacFhionguin (1774-1814) – see the gallery for an extract from the book Bardachd Ghàidhlig.

I have visited Crathie Church and do not recall seeing any graves outside it, but there is a nearby graveyard beyond the post office towards Balmoral which might be worth a look if you are searching for his grave.

Ian Allanach in Deeside Tales

JOHN STEWART, alias IAN ALLANACH

“The battles, sieges, fortunes That I have passed,

I ran it through even from my boyish days,

To the very moment that he bade me tell it.”

—Shakspere.

THE formation of the 87th Regiment or Keith’s Highlanders has already been referred^to. About the end of the year 1759, they joined | the allied army in Germany, under Prince Frederick of Brunswick; and for three years bore a distinguished part in the militaiy operations undertaken by that commander against the French. The appearance of this body of troops, so unlike in dress and manners any soldiers the Germans had hitherto seen, gave rise to various surmises regarding their previous mode of living, and some curiosity was exhibited to learn what it had been. A learned writer in the Vienna Gazette of 1762 undertook to solve the problem; and here is his account—“The Scotch Highlanders are a people totally different in their dress, manners, and temper from the inhabitants of Britain. They are caught in the mountains when young, and still run with a surprising degree of swiftness. As they are strangers to fear.

Although no memory remains of any soldier, belonging to the Highland regiments that embarked for the Franco-American war, returning to his native glen, yet many people on Deeside will recollect that in the above described hamlet, and not in one of its best houses, there lived forty years ago an old man named Ian Allanach, or in English, John Stewart, whose delight it was on the long winter evenings to recount to greedy audiences his adventures in Germany, when a private in Keith’s Highlanders.

Ian, though no boastful hero, was as proud of having served under the Prince of Brunswick as the Laird of Drumthwhacket was of having been a Chevalier under “the immortal Gustavus Adolphus, the “Lion of the North”; and, like that worthy, was in the habit of solving all military problems by an appeal to what his beau-ideal of a warrior had done, or might have been expected to do, in similar circumstances.

It was easy to set the old soldier on his hobby. A reference to any warlike exploit or feat of arms or generalship would suffice to introduce an account of something of a like nature achieved or experienced in the German war; and no battle either in the Peninsular or Continental campaigns of the first Napoleon was equal in his estimation to the action at Fellinghausen. It was characteristic of all his stories that, if they did not begin with an account of this engagement, they were sure in some way or other to lead to it He had so often “fought his battle o’er again,” and in the same unvarying language, that most of his listeners could repeat the narrative almost as accurately as himself. Though the battle story had been told every night in the week, he never tired of it, nor did it ever fail to awaken in him the ardour of the military days of his youth, often to the extent of rendering him oblivious of his present circumstances. This forgetfulness was sometimes taken advantage of by the more youthful and frolicsome of his hearers to play off ludicrous practical jokes upon him, more to amuse the company than to ridicule the mental absentee; for Ian was good-natured and & great favourite with the young.

Nothing provoked him more than to hear Napoleon’s war tactics extolled The world had rung with that warrior’s fame, but Ian disallowed it If any one remarked, “Wisna that good generalship o’ Boney?”

“Good generalship!” Ian would contemptuously exclaim, “if he had advanced that way against the Prince of Brunswick, he would have taught him another lesson.”

Whether Ian Allanach ever became acquainted with the failure of his hero in the campaign of 1792 against revolutionary France, or in 1806 on the disastrous field of Jena against Napoleon, or with his death in the dingy old castle of Altona, is not certain; but if he had heard of them, the knowledge had no influence on his opinion as to the relative merits of the two generals. He remained to the last firm in the belief that Bonaparte was no match for his favourite hero in the art of war.

Ian was fond of society, and the pink of company to him was a good listener. In the winter nights, if no visitors appeared early in the evening at his own fireside, he would go in quest of them to his neighbours’, and where he planted himself for the forenight there was generally no lack of company. Let one fancy to himself the ben, or kitchen end of some auld warl’ house, open to the rafters, and everything above the low walls japanned with smoke, a long settle, with a table, styled a dresser, lining one side, a row of chairs and stools, with the muckle “rin wheel”—often removed in the evening for the sake of room—skirting the other, the seats occupied by the more aged visitors, and the remaining space filled to the door with juveniles as they best could huddle together; the gudeman in the chimney lug on one side of the hearth, and Ian similarly enthroned on the other, and he will have a pretty fair picture of a forenight meeting in the Braes of Micras fifty years ago.

At such time and place the business of the evening generally began with the gudeman asking some question regarding the German war, as,

“Well, Ian, what did the Germans think o’ you Highlanders, when ye went ower among them?”

“I kenna well what they thought,” Ian would reply, “for I never could understan’ their gibberish; but I can tell ye it wisna lang when the Prince o’ Brunswick thocht muckle o’s, an’ I’m sair mistaen if he didna gar his father vrett to his cousin, King George, to thank him for sendan1 sic brave soldiers to him.* But as for the German bodies, it’s my thocht that they took us at first for wild savages, an’ wadna come near’s for fear we would jump upo’ them an’ eat them. They had a sort o’ notion that in our ain country we ran wild among the hills, and that we cu’d hardly be catched ava’, an’ gin we werena taen whan we were young we cu’d never be tamed, but wid tak’ the first chance o’ rinnan’ aff again like mad. But we let them see at Fellinghausen that rinnan’ aff wisna what we were best at”

And then Ian would strike into an animated account of the battle—

“Ah! fine do I mind that nicht i’ the middle o’ summer [15th July, 1761], when after we had taen our supper we received orders to get under arms, and hold ourselves ready to march at a moment’s notice.”

In the battle narrative Ian affected a style above his ordinary mode of expression. His command of English was too poor to serve his purpose, and he had a ludicrous way of giving English accents to Scotch words when compelled to use them. He generally, however, relapsed entirely into his native Doric if he happened to be driven off his usual line of march by a question, or request for an explanation.

“There was a great stir among us,” he would continue, “everybody wondered what was to happen, for we had not heard that the French were near. In about half an hour in there came two dragoons, galloping as hard as they could. They were at once admitted into the commander’s tent, and several officers got orders to be in waiting. Out they came again in about another half hour, and each officer went to his own company and regiment, and then we were filed off at the back o’ supper time along the road. First there were the grenadiers, and we came next This wisna as we ees’t to march, for we an’ the grenadiers were maist aften hin’most; so we thought there must be something bye ordinar’ tae dee.

“We had gone on in this way for eight or nine miles, when in there came more dragoons, galloping like the others. It was now clear day-light, and nothing was to be seen. We then got orders to halt We hadna been here long when we heard, as gin it had been to the south-east o’’s, the sound of a drum; and then came more dragoons, and again we were marched at quick speed for about another mile, the sound of the drums getting louder and louder, and at last we saw colours flying, and begonets glancing nae twa miles awa’. And what was this but an army under the old Duke, that the French were tryan’ to keep from joining us, but we were afore h&n1 wi’ them ! Now both armies had got together in spite o’ them.

“It was thought that after this the French would not attack us, but we were mistaken there. The Prince did not trust to that, and so we were still kept under arms. We didna get ony breakfast that morning, though we had been marching all night.

“Weel, there was a good big hillock on our left as gin it had been half a mile or so in front of where we were halted; and his Highness, and some more officers of the staff took some cavalry and galloped off to the top of it There they stood a good while looking wi’ their spy-glasses and speaking together. When they came back, we Highlanders were immediately marched to the hillock with twelve or fourteen cannons, and artillerymen to work them. We could see a long way along the road, and over the plain a little to the south-west of us, where our men were deploying.

“We had not been long here when we saw two or three dragoons coming galloping along the road, and on they came till they were fired at by the out-posts of our army, and then they retreated. After them others came, now and then, in parties of threes and fours, galloping here, and galloping there. Some o’ them came gey near where we were. After a little they * stopped coming, and then we saw a great stour in the south-east, and by and bye we heard the drums. It was then that General Keith came forward, and says he,

“Now, Highlanders! there’s the French coming. Let me see that ye stand your ground, an’ gie auld Scotland an’ me cause to be proud o’ ye.’

“We gave him a cheer and then stood to arms. By this time we could see the enemy spreading out on the plain, little more than half a mile away. It was not long when they threw out two or three regiments of cavalry; and away they galloped straight north.

“These fellows mean to be at us/ said Keith, ‘ but well be ready for them.’

“We were then drawn up behind the guns, facing to the north-east, with our backs on our own men, so that we could not see what was going on, but in two or three minutes such a noise of cannons got up that you could not hear your own word

“Form to receive cavalry,’ cried Keith; and we had hardly got into squares when they were upon us. On they came, waving their swords.

“Fire!! cried Keith ; and we gave them a volley.

“They reeled a bit; but on they came again faster than ever, and tried to make their horses jump on the points of our begonets. Then they wheeled about and dashed at us again. They did this three or four times, trying to cut some of us down with their swords, and firing pistols in our very faces; but still they could not get in amongst us. Whenever a man fell, another took his place. At last they gave it up for a bad job. But they got at us some way with their cannon, and we had to move our position. Then came the cavalry again, but we gave them such a volley this time that they did not come to close quarters. A great hash o’ them fell, and the rest galloped off. The din at our backs at this time was extraordinar’, but we had not much time to think of it.

“‘Fix begonets, face to the right, double file,’ cried Keith. We had scarcely got into position when the French guards were within musket shot of us. The balls were flying over our heads like hailstones, but they did not kill many, for they could not get at us till they came on to the brow of the hillock. When they did come we made a dash at them with our begonets, and tumbled them back with heavy losses; for, as soon as they turned from the begonet charge, we let drive at them wi’ our musket shot; but just then we got a dreadful volley ourselves, and had to get back to our old position. On they came again, and we played them the same over again, but we did not venture quite so far this time, and did not lose so many men.

“The third time they came on we tried them in a different fashion. We went farther back ourselves, and let them farther on to the riggin. Then we fired our shots first, fixed our begonets, and dashed at them; but now we did not give them time to turn, but down the brae after them helter skelter. They did not think we would do this, for when their second line fired they killed far more of their own men than of ours; and then they turned too, and we after them. They had to cross the line of our cannon, and this put them clean out of order. What happened after this I can hardly tell you, for we were now in the smoke of the battle, and marching forward. Though the French were in full retreat, they were still wheeling round and firing at us; so we got orders to halt, and there was no more fighting that day.

“After we had got to our quarters, Keith comes forward, and says he, ‘You have done nobly to-day, my brave fellows; but the French are not half thrashed yet I think we shall have to beat them again to-morrow.’ We cheered him, as much as to say, ‘We’re ready.’

“All that night we lay on our arms, and after breakfast next morning we marched to the town of Fellinghausen. The road passes through the town, but there the French was posted and had thrown up barricades and planted cannon to keep us out When we came in sight of them a council of war was called and after that Keith comes round where we were, and says he—

“The French mean to let us attack them to-day; there they are wrong. They are bold at making an attack, but they are not so firm at resisting one. Well soon drive them from their position yonder. Now, my lads, at the word of command we’re to storm, and I’m sure we’ll do it gallantly.’

“Two or three batteries were then thrown up, and the cannon began. They played at one another for half an hour or so, and made a terrible noise, but we could not see what execution was done. The French arena bad at long range, but their patience is unco short At last out came a detachment of their army on the north side of the town, as gin they meant to turn our flank, and then we and the Grenadier Guards were drawn up to face them. On they came very boldly, wi’ a regiment of cavalry on their right They were so very grand looking that I thought we were all to be smashed to pieces.

“’Steady, my Highlanders,’ cried Keith, ‘there’s help at hand.’ With that a regiment of our dragoons came trotting up, and took their station on our left On the enemy came, bold as lions, and fired into our lines. A monstrous hash felL Then we gave them our charge, and rushed at them double quick wi’ the begonets. They did not wait for us, but turned back towards the town. We were close at their heels, and in we plunged a’ thegither among their cannon. Two or three regiments o’ Bruns-wickers came up at this time, and we drove the French from their guns at all points. They tried again and again to take them from us, but to no effect At last they came in a strong body up the street, but now our cannon were brought forward and made terrible havoc o’ them.

“‘Now, my lads,’ cried Keith, ‘clear the Gallowgate!’

“With that we down upon them with a great cheer. There was some begonet wark there, I can tell ye. The front o’ the column reeled back. We gave another cheer, and then they ran like mad. But just as they were getting dear o’ the street at the ither end, they were taken in flank by a Prussian regiment, and broken to pieces. Then there was such a pursuing, an’ cheering, an’ roaring, an’ hacking, an’ hashing, as the like was never seen afore or since.

“That was Fellinghausen, sirs, and grim wark it was! ”

“Bo-o-oney!” lan would here contemptuously exclaim, “wi’ his mail dad cuirassiers wad hae deen little there! Pinna tell me. Gin the Prince o’ Brunswick wi’ sic an army as he had that day cu’d hae met him, he wad hae made mice-meat o’ him and his cuirassiers baith.”

Ian’s exdtement had by this time reached the culminating point, and had anyone been hardy enough to question his assertion he would have run no little risk of receiving a tangible proof of the physical powers of the old champion of the Bruns wicker.

“That evening,” Ian would conclude, “General Keith made a speech to us, and thankit us, in the name o’ the Prince o’ Brunswick, for our gallant behaviour. We had little trouble o’ the French for nearly a year after this.”

Though the battle #of Fellinghausen is not the important event in history which it was in the eyes of the old soldier, it was of sufficient consequence to induce the French to withdraw from Westphalia, and had a considerable influence in bringing the Seven Years’ war to a close.

In the general order after the battle the Duke of Brunswick thus refers to the conduct of the troops—“His Serene Highness Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick has been graciously pleased to order Colonel Beckwith to signify to the brigade he has the honour to command his entire approbation of their conduct on the 15th and 16th of July. The soldier-like perseverance of the Highland regiments, in resisting and repulsing the repeated attacks of the chosen troops of France, has deservedly gained them the highest honours. The ardour and activity with which the Grenadiers pushed and pursued the enemy, and the trophies which they have taken, justly entitle them to the highest encomiums. The intrepidity of the little band of Highlanders merits the greatest praise.” Colonel Beckwith adds, “The humanity and generosity with which the soldiers treated the great flock of prisoners they took does them as much honour as their subduing the enemy.” Beckwith was the Brigadier-Commander, but Ian recognised no officer between Keith, the Colonel of his own regiment, and the Commander-in-Chief. Next to the Prince of Brunswick, Colonel Keith was his idol; and through him, and him alone, did he understand all communications were carried on between the regiment and headquarters.

The foregoing is but a brief epitome of Ian’s account of the battle of FelUnghausen. When narrated at length, with all the explanations which his audience required, it usually occupied the whole of a fore-night’s sederunt On the following evenings considerable tact was required to keep any other story he might begin from drifting into this, which, if he once entered upon it, no art could seduce him either to intermit or abbreviate.

“Now, Ian,” the gudeman would lead off, with the intention of keeping the old soldier off his favourite narrative, “you told us last night how you beat the French at Felling-hausen, but didna the French ever get the better o’ you?”

“Ah, weel! I canna say that they ever gained a battle a’ thegither, but ance or twice they were gey hard on’s. I’ve heard it said that they did ance gain something like a battle at a place they ca’ Briggan-up-some (Bergen op Zoom), but that wis lang afore I jined the force. I mind mysel’, though, we had rather the warst o’ a battle, owan’ to some coordly louns o’ Germans that widna’ stan’ up.

“It was i’ the go-hairst, weel on to Hallow-een, a Major Pollox, ane o’ the Grenadier officers, a clever an’ daran’ chiel, took about a hunner o’ his ain regiment, an’ as mony o’ us, an’ ye widna hinder him tae gang an’ beat up the French quarters i’ the nicht time, wi’ the design o’ takan’ the Marshal himseP prisoner. Naebody ever heard tell o’ the like, ’cep’ ance i’ the auld wars atween England and Scotland, when they say the Douglas very nearly caitiet aff the English king fae the mids o’ his ain army. Aweel, as I was sayan’, Pollox, he took twa hunner men wi’ him, an’ awa he gaed to capture the French Marshal. We marched as quiet ’s pussy, an’ managed to get past the ooter sentries unnoticed. But just when we was at the door o’ the house where we kent the Marshal was, the guardsman called out in his ain lan’age, *Kee-wheue?’*

“Pollox made nae answer, but rushed at him wi’ his drawn sword, an’ ran him richt through the heart. But a dyan’ man, they say, is a dangerous man. He turned just as he was fa’an, an’ fired his pistol into Pollox’s breast, an’ baith dropt to the grun’ stock dead. But the firin’ o’ the pistol had given the alarm, an’ we had to cut our way through the enemy back to our ain army. It was a terrible ventursome thing, but we didna lose a man, less poor Pollox.

“Aweel, next day an attack was made on the French. Our regiment was in the front line, an’ up we marched till within musket shot, though their cannon wis blazing at us a’ the time; but then we came to a ditch, an’ a big bank o’ earth on the ither side o’t An’ syne the French, hidan’ behind this bank, opened on us a terrible fire, an’ the Germans turned tail, an’ ran fort. A great lot o’ us were killed, an’ we was mad wi’ rage that we cu’dna get at them. We widna rin, an’ we cu’dna advance, so there we stood firan’ awa’ till our ammunition was nearly done, an’ makan’ naething o’t At last positive orders came f’ae the Prince himsel’, that we should withdraw; an’ our general was blamed for keepan’ ’s so lang there after the rest of the army had retired. But we paid the French back for this at Fellinghausen.

“Ah, fine do I mind that nicht i’ the middle o’ summer, when after we had taen our supper,” and so forth to the end of the narrative, with a march as resolute and unswerving as his conduct had been in the action itself.

IAN ALLANACH – STALKING A SHARPSHOOTER

ANOTHER incident of the war, in which Ian was himself the principal actor, was generally introduced by some one asking how many of the French he supposed he had slain during the campaign. This question, which made the girls of the party stare at him as if he had been an ogre, was generally evaded by himself, but when pressed, notwithstanding that he fenced for a time, it usually led to the following story—

“Weel, ye see, i’ the heat o’ a battle ye dinna ken how many ye kill, or gin ye kill ony ava*. Ye maun do your duty, obey orders, an’ fire awa’ as well as ye can into the ranks o’ the enemy. There’s sae mony fiian’, an’ sic a smoke, an’ stramash, that ye canna tell what effect your shots hae.”

“Ah, but Ian,” some pertinacious questioner would insist, “at a begonet charge ye cudna be in ony doubt”

“That, indeed,” the old soldier would reply, still warding off a question that he had evidently no pleasure in answering, “that, indeed. But the French didna often stan’ up when we charged wi’ the begonet Ony way, it is the pairt o’ brave soldiers to drive a9 afore them in a battle, whatever be the consequence till himsel’ or tae ithers; an9 I canna see that there is ony sin in a man doing his duty as bravely as he can. Only ance had I to do wi9 a business that I9m no vera clear abgut whether it was richt or no.”

All the boys in the company would here eagerly shout— “Tell us the story, Ian; oh, tell us the story.”

“Weel, laddies, though I’m nae vera proud about it, I’ll tell ye how it happened.

“Ye maun ken that the French didna always meet us in fair field as at Fellinghausen, but sometimes they wid get into a fortified town, an’ try to keep their hold there in spite o’s. Now, a fortified town is like this99—and here Ian with the charred end of a splinter of firewood, called a caunle, would sketch upon the hearthstone the fortifications, and the manner of approaching them by means of trenches.

“Weel, ye see,” he would continue, pointing to a particular part of the draught, “as we were working in there ae time, some way or other there wis aye some o9s shot every day, an9 naebody cud fin9 out how it could be. Every plan had been ta’en to protect us f ae the French sharpshooters, but somebody wis aye killed, an9 naebody kent how the shots cud get into the trenches. At lang last it was found out; an9 how do you think it wis? Ane o’ them had got intil a thick tree, an9 wis firan9 at us out among the branches.

“Aweel, the day after it was found out, it was our company’s turn to work where the danger wis; an9 just when we were drawn up, afore we were marched intil the trenches, the Captain, he says, “Is there anybody here who has shot a deer in the forest? Naebody made answer.”

“I’m sure, Ian,” someone who had known John in his ante-military days would remark, “I’m sure, Ian, ye were a good han’ at that ance—why didna ye speak out, man?”

“A body shu’dna be ower rash answeran’ onyhow,” Ian would reply with a show of Scotch caution in the remark, “an’ I’m thinkan’ I micht hae been as weel to hae hadden my tongue a’thegither.

“Howsomever, after waitan’ a little an’ naebody speakan’, I steps forward, an’ says I, ‘Captain, I have,’ says I.

“Follow me,’ says the Captain, an’ then he tak’s me out ower a bit, an’ pointan’ to a clomp o’ heich auld trees near a mill, says he,

“‘Do you think you could stalk these trees?’

“What’s in the trees, Captain?’ says I.

“‘Well,’ says he, ‘I am much mistaken if the French sharpshooter who is killing so many of our men is not commanding our trenches from the top of one of those trees there; and if you think you could stalk him, and bring him down, I promise you it will not be forgotten to you.’

“‘I don’t like the job, Captain,’ says I, ‘for though I have stalked the deer, they’re different Pae sharpshooters. Howsomever, I’ll try, Captain,’ says I.

“I had nae sooner said the word than I began to rue. But it was noo ower late, an’ so I made ready, an’ set out “Ye may be sure I took terrible care, creepan’ f’ae ae hillock to anither, syne at the back o’ a dyke or a hedge till I got in among the trees. There wis ae thing I hadna to notice that wu’d hae spiled me wi’ the deer—I hadna to notice the win’, and that helpit me some. Teetan’ roun’ an auld stump, what shu’d I see but a chiel wi’ three guns hangan’ on the branches aside him, gey weel up the tree, an’ gloweran’ sharp the way o’ our trenches. I thought my vera heart wid loup out, it was duntan’ at sic a rate. It wisna fleg; but I thocht I wisna muckle better than a murderer to snake upon a man that way, an9 shoot him as gin he had been a craw; I thocht it wisna richt Nae but I was puttan’ mysel’ in about as muckle danger as he was in, but for a’ that—.

“I got ready three times an’ aye rued, an9 took down the gun f’ae my shu’der again. At last, thinks I, this’ll no do ava’. I’ll gie him a chance. So I steps out ahint the stump where I wis hidan’, an’ cries up to him, *Tak’ tent, my billy,’ an’ wi’ that I fires at him. Down he came to the gran’ wi’ a thud that wu’d hae killed him though he had been a wild cat, let alane a man.”

The boys at this point in the narrative generally gave vent to their hitherto restrained feeling, by shouting,

“Well done, Ian 1 quite right, quite right! the scoundrel had no business there. Ye gave him a better chance than he deserved. He didna cry to you when he was shootan’ you i’ the trenches, ‘ Tak’ tent, my billies.’ ”

“Maybe, laddies, maybe,” the old soldier would continue, “but I never let my een see him, but off I gaed as fast as I cu’d rin, an’ as good need had, for I was within range o’ the French guns.

“When I got back, the Captain calls me up, an’ says he, ‘Well done, my brave fellow, you will be relieved from trench duty to-day, and here’s a guinea to enjoy yourself.’ I never heard onything mair about it It wisna lang after this when peace was made, an’ we were ordered home, or maybe I micht hae got promotion.”

The boys of the present age, daily surfeited with glowing accounts in their penny or halfpenny newspapers, of sieges and battles where half a million soldiers are engaged, and where the slain of a single day are more in number than the old Duke of Brunswick ever had under his command, may think that their fathers must have been easily amused when in their boyhood they listened with such absorbing attention to Ian’s trifling tales of war. But neither the men nor the boys of the present generation ought to suppose that the military deeds of our fathers were either less heroic, or are less interesting because of the smallness of the armies in which they served, or the primitive character of the arms they used. Individual heroism is most apparent when the numbers are few; and indeed it requires less courage in a man to march to an attack surrounded with ten thousand fellow soldiers, than when he forms one of a thousand, even though the enemy be proportionally small; and the interest attaching to an engagement, in which personal valour is sought for, is in the inverse ratio of the numbers engaged, just as a duel is a more sensational event than the battle of Gravelotte.

Nor ought we to hold of little account the art and means of war in ages past, lest judging so we may be so judged; for who knows that the soldiers of a hundred years hence may not think as little of the battle of Sedan, where a hundred thousand men were made prisoners, of the sieges of Strasbourg, Metz, and Paris, and of our engines of death, chassepots, mitrailleuses, and rifled artillery, as we do of the tattle of Fellinghausen, and the old flint musket? Anyhow, the backward glance may speed the onward march. Nature’s powers are not yet exhausted. If so much had been done in the century past, it will be to our and our children’s disgrace if as much more be not done in the century coming, not, it is to be hoped, in the invention and improvement of engines of destruction, but in the elevation of our race, in the spread of knowledge, and in the cultivation of the arts of peace; so that in the eyes of future generations the history of our wars may appear the monstrous outcome of the savage passions of an ignorant age, and men may marvel how, for the settlement of petty disputes of our rulers, we should have abnegated the function of reason, and in imitation of the most savage of the brute creation bent all our energies to the barbarous expedient of sweeping each other from the earth.

But whatever may be the prevailing sentiments and manners of society on Deeside fifty years hence, with such tales as are above narrated could an old soldier beguile to a whole neighbourhood the dullness of the longest winter evening fifty years ago. This, however, was not to last for aye. “Old age,9’ as the proverb saith, “does not come alone;” and with Ian’s increasing yean came infirmities of which, in his nightly wanderings, he did not always take proper account

One night about Christmas, when the ground was hard with frost, and the paths treacherous with ice, Ian was returning home, late but quite sober. With the aid of his trusty pike-staff, his constant companion in these nocturnal peregrinations, he had managed to overcome the difficulties and escape the dangers of the road, till just before his own door, when, probably feeling himself more at home and getting less guarded in picking his steps, his foot slipped, and from the fall he received, he dislocated his shoulder. For some days he could not be made believe but that his injury was slight, but at length he was prevailed on to send for the doctor, if only to ascertain what was the matter. On being informed that his shoulder was out of joint he replied, “Doctor, I suppose you can easily mend it”

“I must tell you, Ian,” said the Doctor, “I fear it will now be a difficult operation for me, and a painful one for you. You have been too long in sending for me.”

“Just do your duty, Doctor,” replied the veteran, “and never mind me.”

After several ineffectual attempts, the Doctor resolved to send for a brother practitioner to assist him, which caused a delay of some days more, the residence of the nearest medical man being then at Kincardine O’Neil, twenty-two miles distant On his arrival, and in consultation, both expressed a fear that Ian might not be able to endure the operation. As yet Sir James Y. Simpson had not discovered the valuable ansesthetical properties of chloroform; and it is questionable whether Ian would have considered it quite soldier-like to submit to such a method of evading pain, even had it been known. As it was, the medical men knew not well what to do; but one of the neighbours to whom they had stated their difficulty, suggested that they should set Ian to give an account of the battle of Fellinghausen, adding—

“When ance he’s fairly intil the battle, I’se gie ye my lug if he cares a button what ye dee wi’ his airm.”

As this, however unlikely to answer the expectation, was the best thing that could be done in the circumstances, they set about it

“Well, Ian,” said the Doctor, who knew his peculiarities, “this is worse than anything that befel you at Fellinghausen.”

“Maybe sae,” replied Ian, “but it’s little to what happened to mony a biaw lad. Fie 1 fie! Doctor; gin ye had seen Fellinghausen I Ah, fine do I mind that nicht i’ the middle o’ summer, when after we had ta’en our supper,” and so on, the Doctor by well-timed remarks exciting unwonted warmth in the narrative.

The dislocation was not reduced without the greatest efforts; but Ian never once interrupted his story, or allowed an expression of suffering to escape his lips. The first use to which he put the restored arm was to extend it in imitation of Keith, calling out at the same time, “Steady, my Highlanders; there’s help at hand.” Though the time of the medical gentlemen was very precious, lan held them there, as the Ancient Mariner the wedding guest, till the whole story was told, with the addition of an indignant denial of “ Boners ” superiority as a general to the Duke of Brunswick.

Ian survived this accident many years, and told his war tales as usual, but he now less frequently went abroad at night Though his iron frame had withstood the wear of ninety winters, his life might properly be said to have ended with his return from the Seven years9 war. To fight his battles o’er again was the delight, almost the business, of the rest of his days, and grew upon him as he advanced in age, till the scenes of memory had become to him more vividly real than those of sense.

At length his last battle story was told, and about the year 1833 he capitulated to the universal conqueror, and was laid with his kindred dust in the sweet churchyard of Crathie. Though a patriot to his heart’s core, he has shared the fate imprecated by the poet on “the wretch concentred all in self.” He was the last survivor of his family, and few, if any, now living can point out the spot where his ashes repose. There, “unwept, unhonoured, and unsung,” requiescat in pace.

Cattanach – the Ha’ o’ Bellastraid

Deeside Tales also has an interesting tale of the local duine uasal (Highland gent) called Cattanach who lived in the same Clachan of Bellastrade at the same time as Iain :

On the left bank of the bum of Logie, Cromar, there was at the time referred to a small hamlet called Bellastraid, the occupant of the principal house in which, called by way of pre-eminence the Ha’ o’ Bellastraid, was a duineuasal, of the name of Cattanach, who probably exercised some sort of superiority over the inhabitants of the clachan. Cattanach had been out in the ’45, and for this and some other contraventions of the law he was wanted by the authorities in Aberdeen. He had suffered some little annoyance from the attempts made to apprehend him, but these proving futile encouraged him sometimes to put those in quest of him at open defiance, and earned for him the reputation of being a dangerous and reckless character, so that few cared to meddle with him. At length a messenger-at-arms, named Cuthbert, a man as daring as Cattanach himself, and the terror of evil doers far and wide, was despatched from Aberdeen to secure him alive or dead. With the intention of surprising his victim early in the morning, he made his arrival at the hostelry of Milton of Logie, on the opposite bank of the stream, late at night Though he preserved a strict incognito, the object of his visit did not escape the suspicion of some who had marked his arrival, and word was sent to Cattanach that he would better be on his guard, as a very suspicious customer had just made his appearance at the inn.

He received the news in bed, expressed the utmost unconcern, but at early dawn was astir. Having carefully loaded his Culloden musket, he swung it behind his back under his plaid, and sallied forth, making straight for the inn and crossing the bum by the stepping stones.

He found the stranger just in the act of issuing from the door way, and addressed him thus—

“Sharp morning this, sir. What may ye be after to-day?”

“Who are you,” replied Cuthbert, haughtily, “that you claim a right to know?”

“I am Cattanach of Bellastraid, and I believe I have a right to know,” responded the other with defiance in his looks.

Seeing that resistance was intended, Cuthbert drew a horse pistol, and aiming at Cattanach drew the trigger. Whether his weapon had been tampered with over night is not known, but a little flash in the pan was all the result.

“Ha, ha, my man,” said Cattanach, “is that what ye’re after? Well let you see better ga’an graith here.” So saying he swung round the Culloden musket, and shot the officer of the law through the heart

Cuthbert fell right across the threshold, and lay there till due notice of what had happened was sent to the authorities.

It was one of the superstitions of the time that, if the perpetrator of a murder could by any chance see through beneath the body of his victim, he would escape the punishment due to his crime. So flu: from proving always true, this belief had sometimes even led to the detection of the murderer, when he might otherwise have escaped. Cases have been known where, during the funeral of a person who had met his death by foul means, the culprit was detected by displaying some anxiety to look under the coffin.

Cattanach, however, had firm faith in the superstitious notion. It shows how great at that time was the popular sympathy with the most criminal of law-breakers, that Cattanach had but little difficulty in prevailing upon one of his neighbours, a man of the name of MacCombie, tenant of the Davan, to accompany him to the inn, and raise the dead body of Cuthbert that he might see under it Having performed this feat to his satisfaction, he retired to his own house, firmly believing that he had stolen a march on human power and got on the leeside of destiny. Next day, however, the intelligence that a small body of dragoons was approaching rather put his confidence to flight; and he took off to hiding with all speed, succeeded in evading all the parties sent against him, and at last found the means of escaping to a foreign land, a circumstance which the superstitious still aver was owing to his having seen under the body of his victim.

From a belief that an evil fate pursued those that took up their abode in a house once occupied by a murderer, the Ha’ o’ Bellastraid was never afterwards used as a human habitation, but was converted into an outhouse, which, within the recollection of the present worthy tenant, did duty as a barn, and, as he is able to tell, possessed a flight of steps to the door indicative of the height of dignity from which it had fallen.

This state of things could not long continue; the arm of the law was too strong and too active, and a few years brought round a more settled condition. It may be safely affirmed that before ten years from the battle of Culloden had passed, the smouldering embers of the rebellion had died out, leaving behind it only a residuum of sentiment too etherial ever again to move to action.

Henceforth the Macgregors were altered men, mostly distinguishable from their neighbours by a more generally marked duplicity of character, and a more romantic and chivalrous style of deportment Even these traces of their ancient descent gradually softened down, but there were one or two traits that they retained to the last—an innate aversion to manual labour, and a strong desire to act the gentleman. “Shall the sons of Macgregor be weavers?” was as truly the leading sentiment of the race at the opening of the nineteenth as at the beginning of the previous century